How a Saskatchewan Family Dealt with the Pandemic of 1918

North America was affected by a pandemic known as the Spanish Flu from 1918 to 1920. The flu infected 500 million people around the world and of these, up to 100 million people died, killing more people than WWI.

My father, Billy Paton, was born in 1905, so he was a boy of 14 or 15 years when the flu hit his family. Billy lived on a farm about 10 miles northeast of Gravelbourg, SK, on the south side of the Wood River.

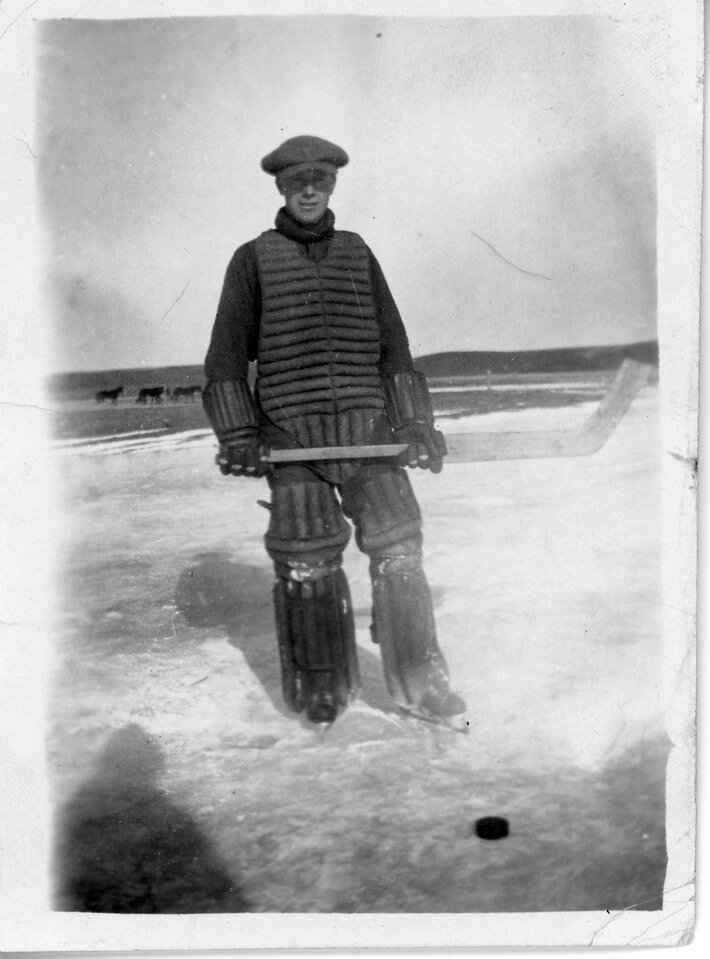

Billy Paton in goalie equipment at Wood River. Photo courtesy of Adrian Paton.

Billy lived with his parents, William and Jemima, his sister Annie (born 1906), brother Bob (born 1908), sister Janet (born 1911) and young sister, Wilhemina (Ina) (born 1914).

Both of his parents became quite ill and were restricted to their beds with the flu. It is likely that some or possibly all of his siblings were also affected. Even if they were not, they were not old enough to be of much help.

His sisters may have helped with the younger children. They could have taken water to their parents or assisted with other small tasks.

Billy did not become ill, so he was responsible for the family and their farm.

The Levitt family lived on a bend in the river about a mile north of the Paton farm. Some old maps classify the Wood River as the most crooked river in the world, so every farm on that river was on a bend.

The Wood River landscape, 1915. Photo of Cliff Bekken hunting bush rabbits. Courtesy of Adrian Paton.

The Levitt parents were bedridden with the flu, so Billy was also put in charge of their family and farm. The Levitt family consisted of five boys. Two of the boys, younger than Billy, were still healthy. They were able to help Billy with some of the chores.

James G. Paton (Billy’s brother) and the Levitt boys. Photo courtesy of Adrian Paton.

Attending to the household chores of two sick families would have been a tremendous responsibility for a young man. He would have been caring for the sick and ensuring that they had adequate food and water. Along with the household chores, there was livestock to be tended to. They had horses, cows and possibly some chickens as well. As a farmer, I can attest to the work involved in keeping livestock fed and watered.

The flu hit the area in the spring of the year, so there would be a shortage of food. The year's supply of potatoes, carrots and turnips would have been much depleted. The canned goods from the previous fall would likely have run out. There was no way that Billy could make a trip to town to get any supplies.

Meat, being a very perishable commodity, would be nonexistent. Billy must have sized up the situation and decided that he would need to butcher a beef. The Levitts had a cow in good condition that he chose to butcher.

My brother Jim recalls what our father told him about this event. It was a two-day affair. Billy likely killed and skinned the animal the first day and then cut it up the second. When you butcher an animal on the farm, it is hung up by the hind legs, and the internal organs, like the stomach, are allowed to slide out. When Jim questioned our father as to how he and a couple of young children could have accomplished this task, he replied: "I just got a saddle horse, threw the rope over a beam and the horse pulled it up."

Butchering beef. Photo courtesy of Adrian Paton.

I imagine Billy's day may have gone something like this. He would rise in the morning and prepare some food for himself and the ill people in the house. He would tend to the other needs of the family, and then he would have headed to the barn to feed and water the animals and milk the cows. I think that there was at least one milking cow at each farm. The cows would have provided them with milk and cream that they could use as a food source. Billy also mentioned that he used some of the cream to churn into butter.

After he had completed these tasks at his farm, he would travel to the Levitt farm to repeat the process. The farm was not far away, but he had to cross a river to reach it. When he recalled the story, he mentioned that he had to cross on the ice. As it was spring and the ice was unpredictable, he carried a long pole for balance in case he broke through. Luckily this did not occur.

The Wood River in Saskatchewan, February 2014. Photo by Mark Eddy.

He was accompanied on these trips by the faithful farm dog; however, on one of his return trips, he noticed that the dog was not with him. He was hopeful that the dog had decided to stay behind with the Levitt family. But the dog was never seen again, so his sure-footed friend had likely slipped beneath the ice.

All members of both families survived the Spanish Flu.

Foot Note

To thank him for his help, the Levitt family, who were horse ranchers and farmers, gave Billy a horse that he rode and drove for many years.

Billy Paton on the horse he received from the Levitt family, 1925. Jack Erskine far left. Photo courtesy of Adrian Paton.

It was one of the horses that he eventually traded to the Johnson brothers of Melaval, SK, for a new Case tractor. The tractor moved him into the machine age of farming, but his love of horses lasted a lifetime.

I have no doubt that Saskatchewan people will survive the pandemic of 2020 as they did a century ago.

Adrian Paton

Adrian Paton began to collect photographs in the late 1980s, when his grandmother’s photograph album was passed down to him. Since then, he has built an enormous photograph collection, totaling about 8,000 pieces. Many of the photos relate to the Arcola region. He has recently worked with The Saskatchewan History & Folklore Society and the University of Saskatchewan to digitize over 1000 of the photos and record his knowledge about them. Adrian has contributed numerous articles to Folklore Magazine. He is the author of the book “An Honest, Genial and Kindly People, a Private Collection of First Nations Photographs from the Turn of the Century in Southern Saskatchewan.” You can learn more about him on his website, www.adrianpaton.com.

“people stories” shares articles from Folklore Magazine, a publication of the Saskatchewan History & Folklore Society. Four issues per year for only $25.00! Click below to learn more or to subscribe.